Eating the Future

Against Torpor.

The Futurist movement has influenced virtually every right-wing avant-garde movement since the 1910s. The most powerful of these, and active today, is the Techno-Optimist movement. But where the Futurists emerged during a period when food insecurity was a national security threat, Techno-Optimists arose in America, a nation that has never known true famine, and today struggles with an excess of calories. This fundamental difference shapes their approaches: where Futurists sought to transform necessity into theatrical passion, Techno-Optimists reduce food to symbol—their complaints about bland and malnutritious foods stand in for broader anxieties about cultural decline.

In the minds of Futurists, Italy was a land of passe-ism. The Italians dreamed of their country's illustrious past and thought too little of its future. For them, one of Italy's redeeming characteristics was its people's love of struggle. And for Futurists, "beauty exists only in struggle." The Italian future would be the land of the avant-garde dreamer and a land which would militarily struggle with itself and with its peers to induce the best in humanity. To heal Italian torpor and to create a new virile, animated, passionate, intelligent man, the Futurists had many treatments - architectural, economic, political, and gastronomic.

Food as National Security

The Futurists' preoccupation with food emerged from genuine crisis. Italy had witnessed Germany's collapse during World War I, where food shortages played a crucial role in their defeat. Like Germany, Italy could not produce enough calories to feed its citizens—it had to import food from abroad. Mussolini's "Battle For Grain" campaign confronted this issue, which promoted autarkic farming and colonial agriculture in Libya.[1] The Futurists, who had always been more theatrical than practical, and who had been relegated to mere supporters of the Fascist movement rather than its protagonists, focused on food as a means of reshaping the Italian people. They believed technology would solve the basic problem of calories, freeing meals to become opportunities for developing Italian passion and creativity.

The Futurists and Techno-Optimists represent opposing aspirations of consumption-related altered consciousness. The Futurists sought the "alcohol of art" - a creative intoxication that would transform Italy into "a race almost entirely composed of artists." They were also no opponent of alcohol, suggesting that liquor, wine, and beer be served at meals.[2] Today's Techno-Optimists prefer the focused clarity of stimulants, reflecting their origins in programming culture where precision trumps passion. Whereas Marinetti wanted to replace "the tiresome alcohol of proletariat taverns" with artistic inspiration, figures like Sam Altman and Marc Andreessen advocate sobriety in pursuit of productivity.[3]

The War on Pasta

The most infamous of the Futurist gastronomic treatments was the fight for the abolition of pasta. It was, effectively, an early culture war. The debate raged across magazines and newspapers. What began as a manifesto became an international media sensation, as bemused foreigners looked on at the Italian infighting. The Chicago Tribune announced "ITALY MAY DOWN SPAGHETTI," while papers from Budapest to Tunisia, Tokyo to Sydney covered what they called the Futurist battle "against sadly wretched foods."[4] The main articles for the abolition of pasta were collected by Marinetti as a part of the "Futurist Cookbook." While the Futurists' "war on pasta" might seem comical, its arguments reflect their anxieties about the state of the Italian nation and its vigor.

First, they argued that pasta was economically harmful—its consumption kept Italy dependent on foreign wheat when they could be promoting more efficient domestic rice.

Second, they claimed that pasta was nutritionally bankrupt. They contrasted Italian pasta with what they saw as the more vigorous diets of northern Europeans: the English with their cod, roast beef, and steamed puddings; the Dutch with their cold cuts and cheese; and the Germans with their sauerkraut, smoked pork, and sausages. In their view, these heartier meat-heavy northern diets produced more dynamic and aggressive peoples. Pasta "does not nourish. It is filling: but it doesn't freshen the blood." Its substance is minimal compared to its volume.[5]

Third, the very method of eating pasta was physiologically damaging. As one supporter, Professor Signorelli, argued: pasta is swallowed rather than properly masticated, forcing the pancreas and liver to compensate for what the saliva should do, creating "an interrupted equilibrium" that leads to "lassitude, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity and neutralism." Pasta was also spiritually corrupting. Its consumption made men "heavy and brutish," leaving them with a "voracious hole... of sadness" that "only a Futurist meal" could fill. Worse still, they declared pasta "anti-virile"—its heavy, bloating effects destroying any "physical enthusiasm" for women. The pasta eater, in their view, was doomed to both physical and spiritual impotence.[6]

Theatrical Meals

The Futurists feared that Italy had become "sentimental, flabby, and slow," with pasta both symbolizing and accelerating this decline. Marco Ramperti, a prominent anti-pastascutti Futurist, argued that pasta had become a weapon for Italy's critics: "It's designed to show up the vanity of our appetite, together with its bestial impetuosity... Our pasta is like our rhetoric, only good for filling up our mouths." For the Futurists, pasta wasn't just poor nutrition—it was a symbol of everything holding Italy back.[7]

Their vision for the perfect meal was theatrical and transformative. First, they demanded "originality and harmony in the table setting," with crystal, china, and décor creating a complete aesthetic experience. Second, they insisted on "absolute originality in the food" itself. They dreamed of chemists developing synthetic fats and proteins that would efficiently deliver nutrition, freeing meals from mere sustenance to become venues for artistic expression.

A Futurist meal would be a multi-sensory performance piece, where "ideal rapid service" and "single successive mouthfuls" could suggest "a love affair or a journey." Where pasta represented mindless consumption—mere "filling up"—these new meals would engage both body and spirit. The dining room would be pervaded by "literary influence," transforming eating from a passive, slop-like activity into an active, artistic experience. This wasn't just about food; it was about creating a new kind of Italian, as dynamic and innovative in their eating as in their thinking.[8]

The Futurist dream of the future of food emerged most vividly in their theatrical "recipes," which were less cooking instructions than avant-garde performance pieces. Their recommendation was that chemists develop synthetic fats and proteins which would provide sufficient calories to allow meals to become theatrical venues of passion and originality rather than simply fulfilling a caloric need. A meal, instead of simply feeding oneself, would amuse all of the senses. The new Futuristic meal will permit a literary influence to pervade the dining room, for with ideal rapid service, by means of single successive mouthfuls, an experience such as a love affair or a journey can be suggested.[9]

Art-Alcohol vs Silicon Valley Sobriety

The Futurists were not teetotalers—alcohol appeared frequently in their meals. But they were more interested in what they called the "alcohol of art," a metaphysical rather than literal intoxication that would spark creativity and transformation. They sought to "eliminate the tiresome, vulgar, and sanguinary alcohol of the proletariat's Sunday taverns" and replace it with an "alcohol of exalting optimism to deify the young, to multiply maturity a hundredfold, and to refresh old age." Their vision was to create an atmosphere of "intellectual art-alcohol" that would transform Italy into "a race almost entirely composed of artists." For the Futurists, alcohol served both as metaphor and material—they contrasted creative intoxication with the stupor of churchgoing masses while incorporating wine, beer, and spirits into nearly every recipe.[10]

This embrace of intoxication and passion stands in stark contrast to techno-optimist attitudes. Where the Futurists sought transcendence through artistic inebriation, today's techno-optimists champion sobriety and stimulants. Their food discourse reflects this divide: while they'll enthusiastically tweet about grilling steaks, they're more likely to praise Adderall than alcohol.[11]

The difference stems partly from their backgrounds—the Futurists were artists and provocateurs, while techno-optimists are programmers and engineers. Artists can chase their passion; programmers need precision or their code won't run. Their dietary concerns reflect this split personality: part Silicon Valley optimization culture, part American conservative anxiety about "seed oils" and "eating ze bugs."[12]

Software Eating the World

Food serves them primarily as metaphor for the Techno-optimists. Take Andreessen Horowitz's motto "Software is Eating the World." When Marc Andreessen wrote this in 2011, it was triumphant—software would eliminate degrading jobs and revolutionize industries. "Many workers will be stranded on the wrong side of software-based disruption," he wrote, but saw this as a necessary step toward progress.

A decade later, the phrase carries different weight. After years of debate about social media's impact on society and questions about whether moving everything online has improved lives, the individuals who compose the developers of this positive view of software, like Marc Andresseen, have developed their thoughts into techno-optimism. Their pivot to "hard-tech" and rallying cry "It's Time to Build" reflect a broader recognition that software alone isn't enough—that Western society needs to create tangible things again.

The War Against Slop

This anxiety crystallizes in the war against "slop." Originally meaning animal feed, it's come to describe any kind of mindless production—especially AI-generated material. It serves somewhat of a counterpart to addiction to the infinite scroll, which induces mindless consumption. Slop, for techno-optimists, is a bit of a metaphysical term. Its definition is loose. Where the Futurists saw pasta as making Italians "heavy" and "brutish," techno-optimists see digital slop making us passive consumers of machine-made mediocrity. As Simon Willison puts it: "If it's mindlessly generated and thrust upon someone who didn't ask for it, slop is the perfect term for it."

But "slop" has become more than just a criticism of AI content. It's their catch-all term for anything they see as degrading standards, and include things as wide as programming in inferior languages to inferior art styles or genres of music or interpretations of quantum mechanics. It effectively can be understood as 'of low quality, could be made by a mindless automaton, such as a LLM.'[13]

One could almost imagine the Futurists, if around today, latching onto the 'slop' war and decrying how pasta - literal slop - is as dangerous of mindless consumption, requiring only slurping rather than conscious eating, as AI slop. The idea that pasta, a standardized, mindless cuisine, is symptomatic of cultural decline, just as techno-optimists view slop-like content as a homogenizing force that flattens creativity into predictable patterns.

Kino vs. Slop

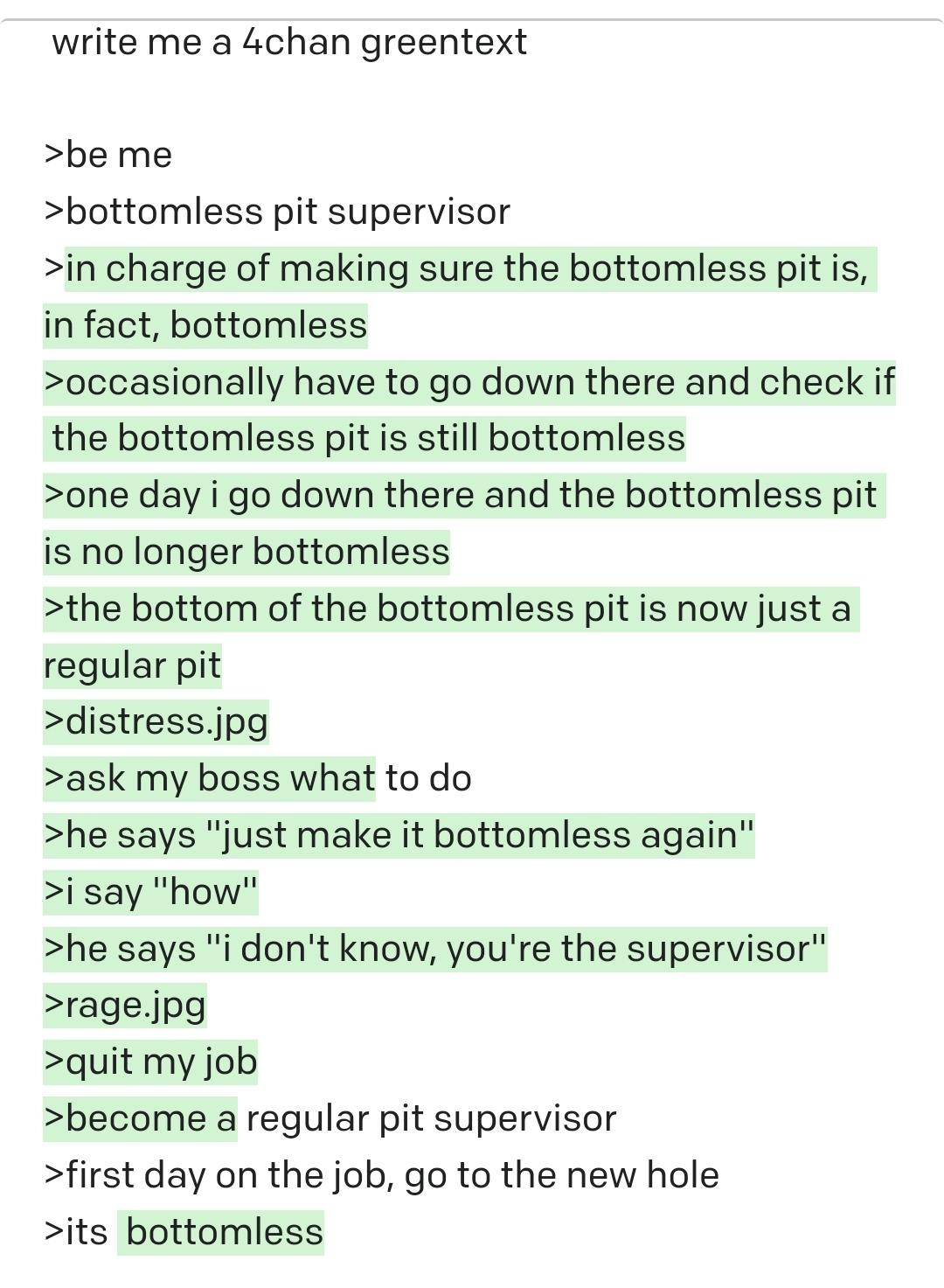

The term's opposite in techno-optimist discourse is "kino," revealing the movement's curious connection to 4chan culture. "Kino" began as a /tv/ board meme about a user misunderstanding his friend's use of the "kino" (Russian & German for "cinema"). The term evolved to mean "highest quality"—Facebook might feed you "slop," but Twitter could provide "kino." In German and Russian, calling a movie "kino" has a similar meaning to calling a movie "cinema" in English - that is a movie of high quality and taste.

Some experiments, especially early ones, have produced moments of unexpected brilliance—like the viral "bottomless hole supervisor" greentext, where GPT-3's unoptimized, jagged outputs created something genuinely novel and compelling.[15] These early systems, less constrained by safety guardrails and normalization, sometimes achieved a raw creativity that today's more polished models struggle to match without considerable effort by users to 'jailbreak' LLMs to act outside the box of standard action.

Yet as AI systems mature, they're increasingly optimized for reliability over creativity. What companies once called "hallucinations"—those weird, unexpected departures from standard responses—are being systematically eliminated in favor of predictable outputs. This mirrors software's evolution: despite early experimental promise, most software eventually coalesced into standardized utilities and attention-harvesting social media platforms. The economics of digital technology favor predictable mediocrity over creative risk. Mindless consumption and production simply scale better, and there's little reason to expect AI will escape this gravitational pull toward slop.

The AI Question

I think the question over whether AI is inherently 'slop' or if it is capable of increasing the sum total 'kino' in the world is actually quite similar to the problem that techno-optimists faced with software 'eating the world.' AI, like software, is intended to get rid of many of the parts of our lives that make us least human—the mindless paperwork, the routine calculations, the mechanical reproduction of content. Yet in automating these tasks, they risk flooding our world with their own form of degraded output. Software gave us infinite scroll and cookie-cutter apps; AI threatens to drown us in synthetic mediocrity. The economics of mindless consumption and production remain too compelling to resist. The question remains whether AI will truly eat the world—and if so, whether it will nourish or merely fill it with slop.

Both the Futurists and the Techno-optimists share a fundamental belief: that technology can liberate humanity from drudgery to pursue higher aspirations. The Futurists dreamed of synthetic foods freeing Italians to become passionate artists; Techno-optimists envision AI automating away mundane tasks so humanity can focus on innovation and creation. Yet both movements face the same paradox—their technological solutions risk creating new forms of mindlessness rather than transcending it.

Assortment of Kino and Slop Posts by Techno-optimists

Bottomless Hole Supervisor

[1] The Battle for Grain, itself, is a fascinating episode of history. While Italy managed to increase its grain harvest, largely through the deployment of tractors and other technological developments, it impoverished Italian farmers, who focused on commodity grain agriculture instead of far more lucrative export-oriented cheese-making and viticulture. Read More: Fascism and Agriculture in Italy: Policies and Consequences, Agricultural Colonization in the Pontine Marshes and Libya

[2] Marinetti, F.T. "Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine." Le Futurisme (1911). In Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman, 91. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

[3] Marinetti, F.T. "Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine." , 92. In Futurism: An Anthology

[4] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, "World Opinion". The Futurist Cookbook. 1933. Translated by Suzanne Brill, edited by Lesley Chamberlain. London: Penguin, 1991.

[5] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, "Against Pasta" The Futurist Cookbook.

[6] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, "Against Pasta" The Futurist Cookbook.

[7] Ramperti, Marco, "World Opinion" The Futurist Cookbook.

[8] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, "The Manifesto of Futurist Cooking". The Futurist Cookbook.

[9] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, "The Manifesto of Futurist Cooking". The Futurist Cookbook.

[10] Marinetti, F.T. "Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine," 92. In Futurism: An Anthology

[11] Waterson, Liz. "Adderall Addiction Amongst California Tech Workers Requires Intensive Treatment." Alta Mira Recovery, February 26, 2018. "American dietary preferences are split across party lines." The Economist, November 22, 2018.

[12] Andreessen, Marc. "On Pausing Alcohol." Andreessen Substack, March 1, 2023. Altman, Sam. "Productivity." Sam Altman's Blog. Syme, Pete. "Elon Musk says he dislikes how 'most alcohol' tastes and makes him feel, but is partial to 'red wine in a fine glass' or a Scotch on the rocks." Business Insider, January 23, 2023. Graham, Paul. "The Acceleration of Addictiveness." July 2010.

[13] See Assortment of Kino and Slop Posts by Techno-optimists

[14] AI and Machine Learning Invade a New York Art Gallery - The Atlantic

[15] See Meme below